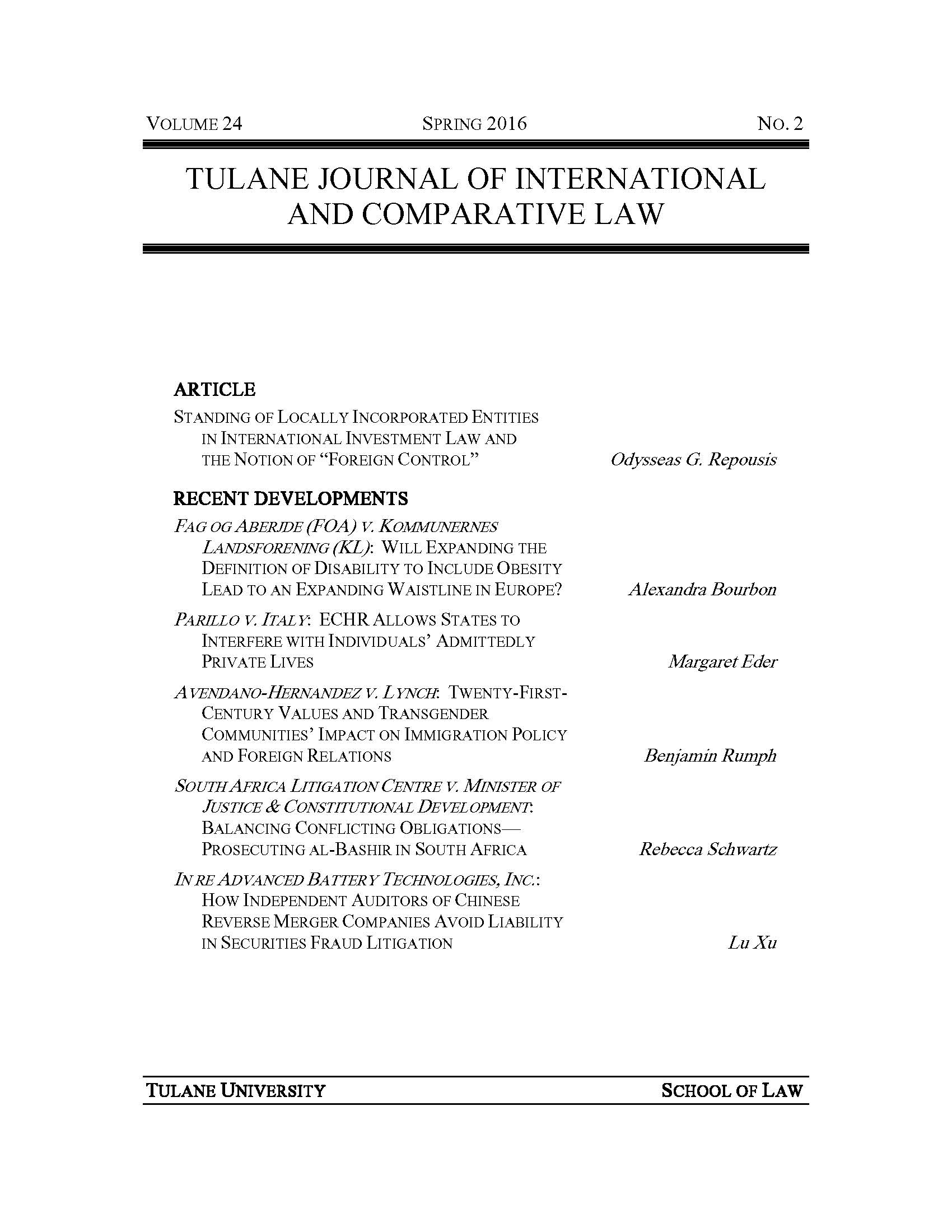

Standing of Locally Incorporated Entities in International Investment Law and the Notion of “Foreign Control”

Abstract

Under customary international law, a state’s ability to espouse the claims of its nationals and

subsequently file a suit against another state is limited by the rule of incorporation.1 This has been

clear at least since the seminal decision of the International Court of Justice in Barcelona Traction,

where it was decided that Belgium could not seek recourse against Spain by espousing the claims

of Belgian stockholders in Barcelona Traction, a Canadian company.2 Equally, claims by locally

incorporated entities against the host state are not possible under customary international law.3 The

strict incorporation test has nevertheless become obsolete, if not thrust aside, by the emergence of

investment treaties. In fact, the unprecedented and drastic change brought about by investment

treaties is all the more evident when considering the whole new array of nationality rules they have

solidified. Investment treaties allow for shareholder claims explicitly or by reference to

shareholding as one of the covered forms of investment.4 Some investment treaties go a step

further by allowing locally incorporated entities to directly file a claim against the host state,

provided that such entities are controlled by nationals or legal entities of the other Contracting

Party.5 Claims by locally incorporated entities are also provided for under the International Centre

for Settlement of Investment Disputes Convention (“ICSID Convention”).6 However, the ICSID

Convention, unlike investment treaties, allows for such claims by reference to a “foreign control”

test. Setting out from this premise, this Article does not intend to touch upon all of the nationality

rules encountered in modern international investment law. Rather, it focuses on the standing of

locally incorporated entities. In particular, it asks whether locally incorporated entities controlled

by nationals of the host state qualify as covered investors, and if so, whether there is a difference

between ICSID and non-ICSID claims. In a nutshell, this Article establishes that when a locally

incorporated entity files a claim against the host state (the state of its incorporation), the operation

of the foreign control test under the ICSID Convention enables an investment tribunal to

unlimitedly pierce the corporate veil and assess whether the locally incorporated entity is ultimately

controlled by nationals of the host state. In this case, an ICSID tribunal will have to deny the

vesting of its jurisdiction because the locally incorporated entity cannot satisfy the foreign control

test.7 This principle was first introduced in 2008 by the tribunal in TSA Spectrum v. Argentina and

has recently solidified in the rulings of Burimi v. Albania and National Gas v. Egypt.8 On the

contrary, when nationals of the host state ultimately control a locally incorporated entity but decide

to file a claim against the host state through an intermediate company, incorporated in the other

Contracting State, the locally incorporated entity is treated as an investment of the intermediate

entity.9 In this case, an ICSID tribunal cannot pierce the corporate veil and assess whether the

intermediate company is ultimately controlled by nationals of the host state.